Many kids and teens are interested in flying, and some even get in trouble with their parents for trying to put their plans into motion.

But Otto Lilienthal, considered by many to be the first true aviator, started building flying machines with his brother as a teen—and he never stopped.

Born in Pomerania, Germany, in 1848, Otto was always fascinated with flight. When he was nineteen, he and his brother Gustav created a fragile flying contraption out of birch veneer.

The wings were 6.5 feet (or two meters), and the brothers planned to strap themselves to the contraption, then take off running down a hill while flapping their arms.

Related Article – Airline Transport Pilot Certificate (ATP): 4 Things You Need To Know

This experiment was unsuccessful, so they built two more flying machines.

Although those didn’t work either, Otto never gave up, aside from taking off for about a year to serve in the Franco-Prussian war.

After the war was over, Gustav decided to pursue a career in architecture, leaving Otto on his own.

With a degree in mechanical engineering from Berlin University, Otto opened a factory that built boilers and steam engines, but he did not give up on his dream.

Instead, he concentrated on studying aerodynamics, focusing in particular on birds and how they flew.

After spending years studying bird wings, he published Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst (Bird Flight as the Basis of Aviation).

In this book, he discussed at length how his data related the importance of lift and wing area to human flight.

He established that birds propel themselves by a twisting or airscrew motion of their outer primary feathers. (This is a principle the Wright Brothers made use of when building their first planes.)

Related Article – 12 Runway Markings and Signs Explained By An Actual Pilot

He also noted that curvature was essential for flight because it created more air resistance than a flat surface.

Having completed all those years of study, Otto finally jumped back into designing and building gliders.

From 1891 to 1896, he accomplished more than 2,000 flights in sixteen different gliders.

By 1892, he’d built a fabric-covered glider with a wingspan of about 31 feet, and could fly it up to about 270 feet.

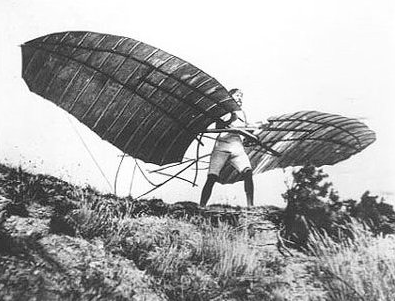

Around this time, high-speed and stroboscopic photography became popular, so there are many pictures of Otto flying in his glider.

These popped up in newspapers around the world, stimulating interest in gliders and human flight and inspiring other aviation pioneers.

In 1894, a US patent application of Otto’s describes how pilots should grip the bar of a glider.

Features of this A-frame design for hang gliders and other ultralight craft are still used in the control frame of some gliders today.

Otto didn’t stop at building gliders, either. In 1894, he constructed an artificial hill to expand his flying space.

There he also placed a dirt-covered shed for storing his flying machines.

He would launch his flights by barreling down the hill and leaping into the wind, gliding about 150 feet.

Eventually he outgrew his artificial hill and moved his operation to Rhinower Hills, a few miles outside of Berlin.

There he often glided for more than 1,150 feet.

Ornithopters fascinated Otto as well, and he eventually moved on to designs with flapping wings.

Related Article – 14 Taxiway Markings, Signs, and Lights Explained By An Actual Pilot

These utilized a lightweight carbonic acid engine that ran at about two horsepower, impressive for its time.

Sadly, his vision of the engine making the wings flap up and down never worked out, and he moved on.

Beginning in 1894, Otto focused on building his ôstandardö glider, a successful monoplane popular with his clients.

Their cambered wings featured ribs that could be folded up for transport.

The fix rear fin and tailplane that freely hinged upward were also very beneficial.

These gliders allowed Otto to glide from 300 feet to about 750 feet.

Otto also added a prellbugel, or rebound bow, to the ôstandardö glider.

This was a flexible hoop fastened from willow that sat in front of the pillow, reducing the impact in the event of a crash.

On one occasion, this saved his life when his glider stalled and nosedived toward the earth.

Unfortunately, when he went out for a flight on August 9, 1896, the glider he chose didn’t have a prellbugel.

It stalled and went into a nosedive, crashing and breaking Otto’s back. He died in a hospital the next day.

His final words were, “Sacrifices must be made.”

As it turned out, his sacrifices helped many other pioneers in aviation later on.

At the time of his death, Otto was working on ways to control or direct the gliders.

The only way he had to do this was by contorting his lower body, which hung free while the rest of him was strapped into the glider.

Known as “the father of flight,” his writings were translated and studied by aviators around the world.

Related Article – 5 Best Low Time Pilot Jobs With 250 Hours

He consulted with Samuel Langley of the Smithsonion Institute and N. J. Shukowsky, a Russian aerodynamics expert.

As the first person to launch himself into the air, fly, and land safely, Otto Lilienthal provided inspiration for many interested in flying.